from Edmund S. Higgins, Medical University of South Carolina

The possibility of having valuable items hidden in secret chambers can really stimulate the imagination. Mid 1960s, British engineer Godfrey Hounsfield wondered if one could discover hidden areas in Egyptian pyramids by capturing cosmic rays passing through invisible void.

He stuck to this idea over the years, which can be described as “look into a box without opening it“Ultimately, he figured out how to use high-energy rays to reveal what is invisible to the naked eye. He invented a way to look inside the hard skull and get an image of the soft brain in it.

The first computed tomography image – a CT scan – of the human brain was taken 50 years ago, on October 1st, 1971. Hounsfield never made it to Egypt, but his invention took him to Stockholm and Buckingham Palace.

An engineer’s innovation

Godfrey Hounsfield’s early life did not suggest that he would achieve much at all. He wasn’t a very good student. As a little boy his teacher described him as “fat”. “

He joined the British Royal Air Force at the beginning of World War II, but was not a great soldier. However, he was a wizard with electrical machines – especially the one reinvented radar that on dark, overcast nights it would help the pilots find their way home better.

After the war, Hounsfield followed his commandant’s advice and graduated as an engineer. He did his job at EMI – the company became better known for selling Beatles albums, but began as an electrical and music industry with a focus on electronics and electrical engineering.

Hounsfield’s natural talents led him to lead the team that built the UK’s most advanced mainframe. But in the 1960s, EMI wanted to get out of the competitive computer market and didn’t know what to do with the brilliant, eccentric engineer.

While on a forced leave to ponder his future and what he could do for the company, Hounsfield met a doctor who complained about the poor quality of brain x-rays. Simple x-rays show wonderful details of bones, but the brain is an amorphous lump of tissue – everything looks like fog on the X-ray. This got Hounsfield to ponder his old idea of finding hidden structures without opening the box.

A new approach reveals the previously unseen

Hounsfield formulated a new way to approach the problem of mapping the interior of the skull.

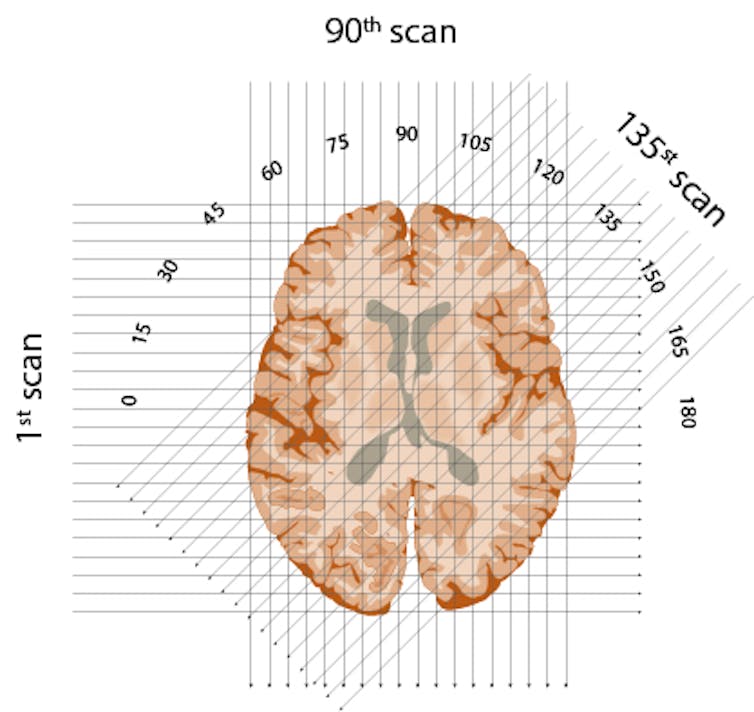

X-rays shine through each “slice” of the brain, oriented in a semicircle at any degree from 1 to 180 degrees.

Edmund S. Higgins, CC BY-ND

First, it would be conceptual Divide the brain into successive layers – like a loaf of bread. Then he planned to run a series of x-rays through each layer and repeat this for each degree of a semicircle. The strength of each ray would be sensed on the opposite side of the brain – with stronger rays indicating that they had traveled through less dense material.

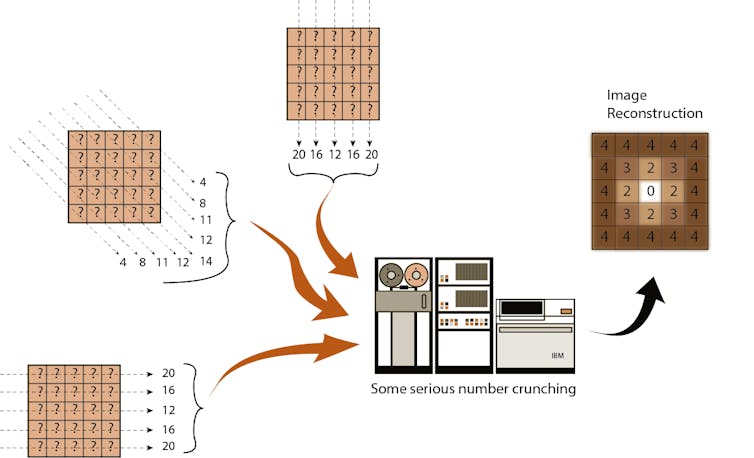

If you calculate the strength of each X-ray beam once it has passed the object and work backwards with an impressive algorithm, it is possible to create an image.

Edmund S. Higgins, CC BY-ND

Finally, in what is perhaps his most ingenious invention, Hounsfield created an algorithm to reconstruct an image of the brain based on all of these layers. By working backwards and using one of the fastest new computers of the era, he was able to calculate the value for every little box of every layer of the brain. Eureka!

But there was a problem: EMI was not involved in the medical market and had no desire to enter. The company allowed Hounsfield to work on its product, but on a tight budget. He was forced to rummage through the research facility’s junk bin and put together a primitive scanning machine – small enough to sit on a dining table.

Even with successful scans of inanimate objects and later, kosher cow brains, the powers at EMI remained underutilized. Hounsfield had to find outside funding if he was to proceed with a human scanner.

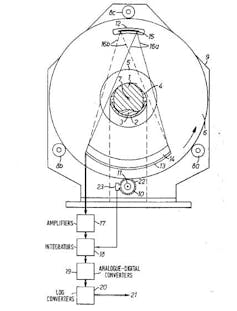

Schematic of the CT scanner contained in the Hounsfield US patent.

Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield

Hounsfield was a brilliant, intuitive inventor, but not an effective communicator. Fortunately, he had a personable boss, Bill Ingram, who saw the value of Hounsfield’s proposal and struggled with EMI to keep the project afloat.

He knew there weren’t any grants they could get quickly, but argued that the UK Department of Health and Welfare could buy equipment for hospitals. Miraculously, Ingram sold them four scanners before they were even built. So Hounsfield organized a team and they tried to build a safe and effective human scanner.

In the meantime, Hounsfield needed patients to try out his machine. He found a reluctant neurologist willing to help. The team installed a full-size scanner in the Atkinson Morley Hospital, London, and on October 1, 1971, they scanned their first patient: a middle-aged woman who showed signs of a brain tumor.

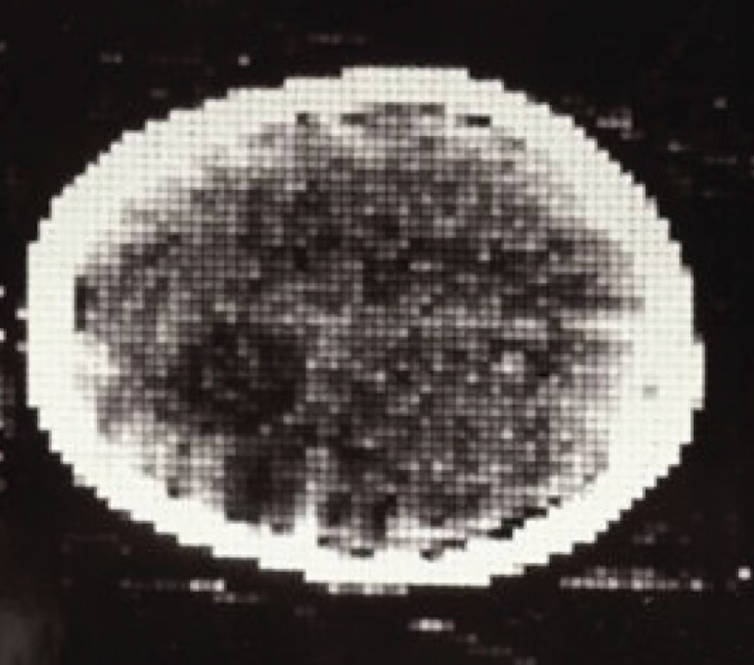

It wasn’t a quick process – 30 minutes for the scan, a trip across town on the magnetic tapes, 2.5 hours of processing the data on an EMI mainframe computer and capturing the image with a Polaroid camera before heading back to the hospital.

The first clinical CT scan to show the brain tumor as a darker spot.

“Medical Imaging Systems: An Introductory Guide”, Maier A, Steidl S, Christlein V, et al., Editors., CC BY

And there it was – in her left frontal lobe – a cystic mass about the size of a plum. This made any other method of brain imaging obsolete.

Millions of CT scans every year

EMI, with no experience in the medical market, suddenly had a monopoly on a machine in high demand. It jumped into production and was initially very successful in selling the scanners. But within five years, larger, more experienced companies with more research capabilities like GE and Siemens were producing better scanners and devouring sales. EMI eventually left the medical market – and did became a case study why it can be better to work with one of the greats rather than trying it alone.

Hounsfield’s innovation changed medicine. He shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1979 and was knighted by the Queen in 1981. He continued tinkering with inventions until his last days in 2004 when he died at the age of 84.

1973, American Robert Ledley developed a full body scanner that could map other organs, blood vessels and of course bones. Modern scanners are faster, offer better resolution and, above all, with less radiation exposure. There are even mobile scanners.

By 2020, technicians carried out more than 80 million scans annually in the US. Some doctors argue that the number is exaggerated and perhaps a third is unnecessary. That may be true, but the CT scan did has been good for your health from many patients around the world, helps identify tumors and determine if surgery is needed. They are especially useful for quickly finding internal injuries after accidents in the emergency room.

And do you remember Hounsfield’s idea about the pyramids? 1970 placed scientists Cosmic Radiation Detectors in the lowest chamber of the Chephren pyramid. They concluded that there was no hidden chamber in the pyramid. In 2017, another team placed cosmic ray detectors in the Great Pyramid of Giza and found a hidden but inaccessible chamber. It is unlikely to be explored anytime soon.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Edmund S. Higgins, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina

This article is republished by The conversation under a Creative Commons license. read this original article.

.

Thank You For Reading!

Reference: www.healthywomen.org